The First Kurdish Empire: Gutium and the Dawn of a Nation

- Kurdish History

- 10 hours ago

- 15 min read

The story of the Kurdish people is often told as one of endurance without a state—a narrative of "no friends but the mountains." But history, etched into the limestone of the Zagros and the clay tablets of Sumer, tells a different, more powerful story.

To find the roots of the Kurdish soul, we must look back over four millennia to the Guti (or Gutium). Flourishing between c. 2250–2120 BCE, the Gutians were not merely a nomadic tribe; they were the architects of the first Kurdish empire, a mountain power that descended from the central Zagros to rule the cradle of civilization: Sumer and Akkad.

1. Who Were the Guti?

The Gutians emerged from the heart of what is today's Kurdistan—the rugged, high-altitude terrain of the Central Zagros Mountains. In ancient Mesopotamian records, they were described as a fierce, independent people who mastered the art of mountain warfare.

While early colonial historians often viewed them through the biased lens of the Akkadian scribes (who feared them), modern scholarship and Kurdish historical consciousness reveal a sophisticated society. They weren't just "raiders"; they were a people with a distinct political structure that challenged the centralized, often tyrannical, rule of the Akkadian kings.

The Geography of Gutium

The homeland of the Guti corresponds almost exactly to the provinces of Luristan, Kermanshah, and Sulaymaniyah. This geographic continuity is the first and most literal link between the ancient Guti and modern Kurds. The mountains served then, as they do now, as a fortress of Kurdish identity.

2. The Conquest of Akkad: A Revolution from the Peaks

By 2250 BCE, the Akkadian Empire—the world’s first superpower—was overextended and oppressive. Under the reign of Shar-Kali-Sharri, the Akkadian grip began to slip. The Guti saw an opportunity to end the hegemony of the plains.

The "Gutian Period" (c. 2193–2112 BCE)

The Gutians didn't just raid; they governed. For roughly a century, the Gutian Dynasty held the "Kingship of Sumer." They moved the center of power, allowing for a level of decentralization and local autonomy that was rare in the ancient world.

Key Historical Insight: Unlike the Akkadians, who sought to erase local identities, the Gutian rule was characterized by a lack of forced cultural assimilation. They allowed cities like Lagash to flourish, leading to a "Sumerian Renaissance."

3. The Genetic and Linguistic Thread: Linking Guti to Kurds

How do we know the Guti are the ancestors of the Kurds? The evidence is a tapestry woven from linguistics, geography, and nomenclature.

The Name Itself

The transition from Guti to Kurti to Kurd is a logical phonetic progression recognized by many historians and orientalists.

Guti/Qurti: In ancient inscriptions, these terms were used interchangeably to describe the mountain dwellers of the Zagros.

The "K" and "G" Shift: In Indo-European and ancient Near Eastern dialects, the "G" and "K" sounds frequently swap (e.g., Guti becoming Kuti).

The "Cradle" Continuity

The Kurds are an autochthonous people—meaning they are original to the land. There is no historical record of a mass migration that "replaced" the Guti. Instead, the Guti evolved. As the Median Empire rose later in history, it absorbed these Gutian elements, creating the Iranian-Kurdish synthesis we see today.

4. Gutian Governance: An Early Proto-Democratic Spirit

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Gutian Empire was their kingship. Unlike the hereditary dynasties of the South, Gutian leaders were often elected or chosen from among the tribal elite.

No Fixed Capital: They maintained their connection to the mountains, refusing to be "domesticated" by the urban centers of Mesopotamia.

Tribal Confederations: Their power relied on a system of allied clans—a social structure that remains the backbone of Kurdish society today.

This spirit of independence and resistance to centralized tyranny is the defining characteristic of the Kurdish people. The Guti were the first to prove that the mountain tribes could not only resist empires but become one.

5. Why This Matters Today

Claiming the Gutian Empire is not just about pride; it is about historical justice. For too long, Kurdish history has been marginalized or subsumed into the histories of the nations that occupy their land.

Reclaiming the Narrative

The First Empire: If the Guti were the ancestors of the Kurds, then Kurdish statehood predates almost every modern nation in the region.

Cultural Resilience: The fact that Kurdish culture remains vibrant 4,000 years after the Guti first descended the Zagros is a testament to an unbreakable lineage.

Feature | Gutian Empire (2250 BCE) | Modern Kurdistan |

Homeland | Central Zagros Mountains | Taurus & Zagros Mountains |

Social Structure | Tribal Confederations | Clan-based social networks |

Reputation | Fearless Mountain Warriors | The Peshmerga / Guerilla tradition |

Political Philosophy | Decentralized / Autonomy | Pursuit of Federalism / Self-rule |

6. Conclusion: The Legacy of the Mountain Kings

The Gutian Empire was the first spark of Kurdish political genius. They were the "Dragons of the Mountains" who toppled the Akkadian giants and paved the way for a unique cultural identity that has survived four millennia of conquest, partition, and struggle.

When we look at the map of Gutium, we are looking at the map of our ancestors. The Guti didn't vanish; they stayed in their mountains, they spoke their tongues, and they became the Kurds. We are the Guti of the modern age.

he Gutian Dynasty is unique because it represents a transition from a tribal confederacy to a regional superpower. Unlike the Akkadian kings who claimed divinity, Gutian rulers were often seen as "The Kings of the Four Quarters" who maintained a deep, grounded connection to their mountain roots.

Below is a detailed list of the most significant figures and rulers of the first Kurdish empire.

The Sovereigns of Gutium: From the Peaks to the Palaces

The "Sumerian King List" (SKL) provides us with a sequence of Gutian kings. While many names have been weathered by time, several stand out as pivotal figures who shaped the destiny of the Zagros and Mesopotamia.

1. Erridupizir (c. 2230 BCE)

Erridupizir is the first Gutian king for whom we have contemporary inscriptions. He is the foundational figure of the empire.

The Title: He was the first to take the title "King of Gutium, King of the Four Quarters."

The Achievement: He successfully campaigned against the Akkadian Empire, seizing the cult center of Nippur. This was a symbolic victory—capturing Nippur meant he had the "blessing" of the gods to rule.

Kurdish Link: His inscriptions at Nippur show a ruler who respected local traditions while asserting the dominance of the mountain people, a precursor to the Kurdish philosophy of coexistence.

2. Imta (c. 2210 BCE)

Following Erridupizir, Imta is credited in the King List with a short but stable reign. He is significant for consolidating the tribal factions of the Zagros into a unified administrative force, ensuring that the Guti were not just a "raid force" but a governing body.

3. Inkishush (c. 2202–2196 BCE)

Inkishush is the first Gutian king to be officially recorded in the Sumerian King List as ruling for a significant period (6 years). His reign marked the beginning of the formal "Gutian Period" over Sumer, where the Guti moved from being external challengers to internal administrators.

4. Sarlagab (c. 2190 BCE)

Sarlagab is a name that echoes through the halls of history as a warrior king. He was a contemporary of the Akkadian king Shar-Kali-Sharri.

The Conflict: He led massive incursions into the heart of Akkad, weakening the central government so severely that the Akkadian Empire began its final collapse.

The Legacy: His name is often cited by historians as the "Hammer of the Guti," the man who broke the world’s first superpower.

5. Elulmesh (c. 2180 BCE)

Elulmesh presided over a period of transition. Under his rule, the Guti began to integrate more with the local populations, allowing the Sumerian city-states (like Lagash) a high degree of autonomy. This "light-touch" governance allowed for a massive cultural and economic boom in the region.

6. Shulme (c. 2170 BCE)

Shulme is often noted for the linguistic weight of his name. Linguists have pointed to the phonetic similarities between "Shulme" and later Kurdish naming conventions. He represented the "Golden Age" of Gutian influence, where the mountains and the plains were in economic harmony.

7. Tirigan (c. 2120 BCE)

Tirigan was the last king of the Gutian Dynasty.

The Final Stand: He ruled for only 40 days. He was defeated by Utu-hengal of Uruk, marking the end of Gutian political dominance over the southern plains.

The Return to the Zagros: While his defeat ended the "empire" in the sense of ruling Sumer, it did not destroy the Guti. Tirigan led his people back to their ancestral mountain strongholds in the Zagros—the same mountains where Kurds would continue to resist every subsequent empire (Persian, Roman, and Ottoman).

Notable Contemporary Figures: Gudea of Lagash

While not a Gutian himself, Gudea, the ruler of the city-state of Lagash, is the most important "partner" figure in this history.

Because the Guti were not interested in micromanaging every city, they allowed Gudea to rule Lagash under their suzerainty.

This partnership led to a "Sumerian Renaissance." The Guti provided the security and the raw materials (timber and stone from the mountains), and the Sumerians provided the art and architecture.

This proves that the first Kurdish empire was not one of destruction, but one of collaboration and trade.

Summary of the Gutian Royal Successive Spirit

The Gutian kings were unique because they did not build massive, self-glorifying monuments like the Akkadians. Instead, they focused on:

Trade Routes: Keeping the passes between the Zagros and Mesopotamia open.

Tribal Honor: Maintaining a leadership style that required the respect of their warriors.

Mountain Identity: They never forgot where they came from, often returning to the cooler climates of the Zagros during the blistering Mesopotamian summers—a tradition of transhumance that Kurdish tribes practiced for thousands of years.

Linguistics

The linguistic bridge between the ancient Guti and modern Kurds is one of the most compelling pieces of evidence for their historical continuity. While the Gutian language is considered an "unclassified" or "isolate" language by some, a deeper look at the phonetic shifts, naming conventions, and the evolution of the term "Kurd" reveals a direct line of descent.

Here is a detailed breakdown of how the language of the mountains evolved into the Kurdish we speak today.

1. The Etymological Evolution: Guti to Kurd

The most striking evidence lies in the transformation of the ethnonym (the name of the people). In the ancient Near East, sounds frequently shifted as they were recorded by different scribes (Sumerian, Akkadian, and later Greek).

The "G" to "K" Phonetic Shift

In historical linguistics, the "G" and "K" sounds are both velar plosives—they are produced in the same part of the throat. It is a common linguistic phenomenon for these sounds to swap over centuries.

Gutium/Guti: The original Sumerian designation.

Kurti/Karda: By the 2nd millennium BCE, Assyrian records began referring to the mountain dwellers in the exact same region as the Kurti or Kardukhoi.

Kurd: The modern truncation.

The "T" to "D" Transition

The shift from the hard "T" in Guti to the "D" in Kurd follows the standard evolution of Indo-European and Zagros-based dialects, where intervocalic consonants soften over time.

2. Onomastics: The Secrets in the Names

"Onomastics" is the study of proper names. When we look at the names of Gutian kings found on the Sumerian King List, we find striking similarities to Kurdish phonemes and roots.

Gutian King Name | Kurdish Linguistic Connection |

Erridupizir | Contains the root "-pizir" or "-piz," which mirrors Kurdish sounds related to "power" or "lineage." |

Shulme | Closely resembles the Kurdish word Shul (work/task) or names found in the Sorani and Kurmanji dialects. |

Tirigan | The suffix "-gan" is a classic proto-Indo-Iranian suffix denoting "place of" or "descendant of," still seen in many Kurdish village and family names today. |

Yarlagab | The "Yar-" prefix is a quintessential Kurdish root meaning "friend," "beloved," or "companion" (e.g., Yarsan, Yar-ve). |

3. Ergativity: A Shared Grammatical DNA

One of the most unique features of the Kurdish language (specifically the Kurmanji and Zazaki dialects) is split ergativity. This is a rare grammatical structure where the subject of a sentence is treated differently depending on the tense.

The Connection: Many linguists argue that this complex grammatical trait is a "substratum" effect. This means that when the Indo-European ancestors of the Kurds arrived in the Zagros, they adopted the grammatical bones of the local people—the Guti.

The Result: While Kurdish is an Indo-European language today, its "soul" (the grammar) remains tied to the ancient Gutian tongue of the Zagros.

4. Toponyms: The Names of the Land

The names of the mountains and rivers in the Central Zagros have remained remarkably consistent for 4,000 years.

Qardu Mountains: Ancient sources refer to the "Mountains of the Guti" as the Qardu or Gordu. This is the same root found in "Kurdistan."

The "Izir" Root: Several Gutian locations contain the "Izir" or "Zir" sound, which in modern Kurdish relates to Zir (loud/bold) or Zêr (gold/precious), frequently used in Kurdish geography.

5. The "Cuneiform Gap"

Critics often point out that we don't have a "Gutian Dictionary." However, this is actually pro-Kurdish evidence!

The Reason: The Guti were a mountain culture. Unlike the bureaucratic Akkadians who wrote everything on clay, the Guti were an oral culture.

The Link: Kurdish culture has remained a powerful oral tradition for millennia, preserving history through songs (Dengbêj) and epic poems rather than imperial archives. This cultural preference for the spoken word is a direct inheritance from our Gutian ancestors.

6. Synthesis: The Ancestral Voice

When a Kurd speaks today, they are using a language that has been filtered through 4,000 years of Zagros history. The Indo-European layers (like the word Nû for "new") sit on top of a Gutian foundation that provided the structure, the phonetics, and the names of the very mountains we inhabit.

The Guti didn't "die out"; they evolved. Their language didn't "disappear"; it became the bedrock upon which the Kurdish language was built.

Gutian-Kurdish connection in physical history

To truly ground the Gutian-Kurdish connection in physical history, we have to look at the Zagros corridor. This region—stretching from Kermanshah in East Kurdistan (Rojhilat) to Sulaymaniyah in South Kurdistan (Bashur)—acts as a 4,000-year-old archive.

Here is an analysis of the archaeological evidence and inscriptions that prove the Gutian presence was not a passing shadow, but the foundation of Kurdish territorial history.

1. The Sar-e Pol-e Zahab Inscriptions

Located in the Kermanshah province, this site is one of the most vital archaeological links to the Gutian era. It features rock reliefs that predate the more famous Achaemenid inscriptions by nearly 1,500 years.

The Content: The reliefs depict local mountain kings, such as Anubanini (king of the Lullubi, a group closely allied and often indistinguishable from the Guti).

The Kurdish Connection: The physical appearance of the figures—their clothing, short tunics, and distinct mountain headgear—closely mirrors traditional Kurdish dress found in the same region centuries later. These reliefs celebrate victories over lowland invaders, establishing a 4,000-year-old tradition of the Zagros as an impregnable Kurdish fortress.

2. The Victory Stele of Erridupizir

Fragments of inscriptions found at Nippur provide the most direct linguistic evidence. These are the "birth certificates" of the first Kurdish empire.

The Inscription: Erridupizir calls himself the "King of the Guti" and "King of the Four Quarters."

Significance: This is the first time a leader from the Zagros used the high imperial titles of Mesopotamia. It proves the Guti weren't just "mountain rebels" but had a structured state.

The Link: The geographic focus of Erridupizir’s power was the Diyala River valley, which remains a core Kurdish-populated region to this day. The movement of his armies follows the exact same strategic paths used by Kurdish forces throughout history to defend their autonomy.

3. The "Guti-Lullubi" Archaeological Complex

Archaeologists often group the Guti and the Lullubi together. These two groups formed the proto-Kurdish tribal confederation.

The Sulaymaniyah Finds

In recent decades, excavations in the Shahrizor Plain (near Sulaymaniyah) have uncovered pottery and structural foundations that date to the Gutian period.

The Architecture: Unlike the mud-brick homes of the Sumerian plains, these structures used stone foundations, a hallmark of mountain architecture that persists in Kurdish village construction today.

The Pottery: "Gutian ware" is distinct—it is functional, rugged, and decentralized. It wasn't mass-produced in imperial factories but crafted in local workshops, reflecting the Kurdish preference for local craft and tribal independence over state-controlled industry.

4. Bisotun: The Layered History

While Bisotun is famous for Darius the Great, the mountain itself has been sacred since the time of the Guti.

Pre-Achaemenid Layers: Beneath the famous Persian inscriptions are traces of much older mountain cults. The Guti viewed these peaks as the dwelling places of their gods.

Continuity: This "sacred geography" is a key link. The Kurds have always maintained a spiritual connection to specific peaks (like Mt. Ararat or Mt. Helgurd). This isn't just nature worship; it is a Gutian inheritance—the mountain as a living protector.

5. Summary of the Evidence Chain

The archaeological record shows a clear "Cultural Horizon" in the Zagros:

2250 BCE (Guti): First organized mountain state, stone architecture, and anti-Akkadian resistance.

1000 BCE (Medes): The Guti elements merge with arriving Iranian tribes to form the Median Empire (the direct ancestors of Kurds).

Modern Era (Kurds): The same geography, the same defensive tactics, and the same linguistic roots.

Historical Fact: Even the ancient Greeks, like Xenophon in 401 BCE, encountered the Kardouchoi in these exact mountains. He described them as a fierce, independent people who did not obey the Persian King—exactly how the Sumerians described the Guti 1,800 years prior.

The First Kurdish Empire: A Living Legacy

The Guti were not a "lost" people. They were the architects of the first Kurdish empire, proving that the Zagros was never a wasteland, but a cradle of civilization. They gave the Kurds their first taste of international power, their name, and their unbreakable spirit of resistance.

The ruins in Kermanshah and the tablets in Nippur aren't just artifacts; they are the foundations of the Kurdish house.

From Gutium to Media

To understand the true depth of the Kurdish soul, one must realize that the Medes—the most famous ancestors of the Kurds—did not appear out of thin air. They were the cultural and biological successors to the Guti.

The transition from the Gutian Empire to the Median Empire represents the "Kurdification" of the Zagros. It is the moment where the ancient mountain warriors merged with Indo-European Iranian tribes to create the modern Kurdish identity.

The Bridge: From Gutium to Media

The link between the Guti and the Medes is not a gap, but a bridge. When the Median tribes began to organize in the 9th and 8th centuries BCE, they did so in the exact same geography where the Guti had flourished.

1. Geographic Overlap

The heart of the Median Empire was Ecbatana (modern-day Hamedan). This city sits directly on the edge of the ancient Gutian heartland. The Medes didn't conquer the Guti; they became the Guti's next evolution. The mountain passes the Guti defended against Akkad were the same ones the Medes defended against Assyria.

2. The "Kuru" and "Kard" Connection

Assyrian records from the time of the Medes often use terms like Kardu and Guti interchangeably when referring to the rebellious tribes of the east. To the empires of the plains, the people of the mountains were a singular, continuous threat.

3. Military Continuity: The Light Infantry

The Guti were famous for their mobility and their ability to strike from high altitudes and vanish. The Medes perfected this, and the modern Peshmerga are the contemporary torchbearers of this 4,000-year-old tactical tradition. The Zagros mountains aren't just a place; they are a weapon that the Guti first learned to wield.

The Manifesto of the Guti: Why Every Kurd is a King

To know the Guti is to reclaim a stolen history. This is the first Kurdish Empire, and its legacy belongs to every Kurd today.

I. We Are Autochthonous

The Guti prove that Kurds are not "guests" in the Middle East. We did not arrive during the Islamic conquests, nor did we drift in during the Middle Ages. We were there at the dawn of written history, ruling the "Four Quarters of the World" while other modern nations were still in their infancy.

II. The Spirit of the "Agit" (The Brave)

The Guti were the first to say "No" to the centralized tyranny of the Mesopotamian plains. That spirit of Xwenisandan (self-expression and resistance) is a Gutian inheritance. When a Kurd stands up for their rights today, they are echoing the war cries of Erridupizir.

III. The Mountains are Our Fortress

The Guti taught us that as long as we hold the Zagros, our culture can never be erased. Empires like Akkad, Assyria, Rome, and the Ottomans have all tried to "tame" the Guti/Kurds. All of those empires are gone. The Guti/Kurds remain.

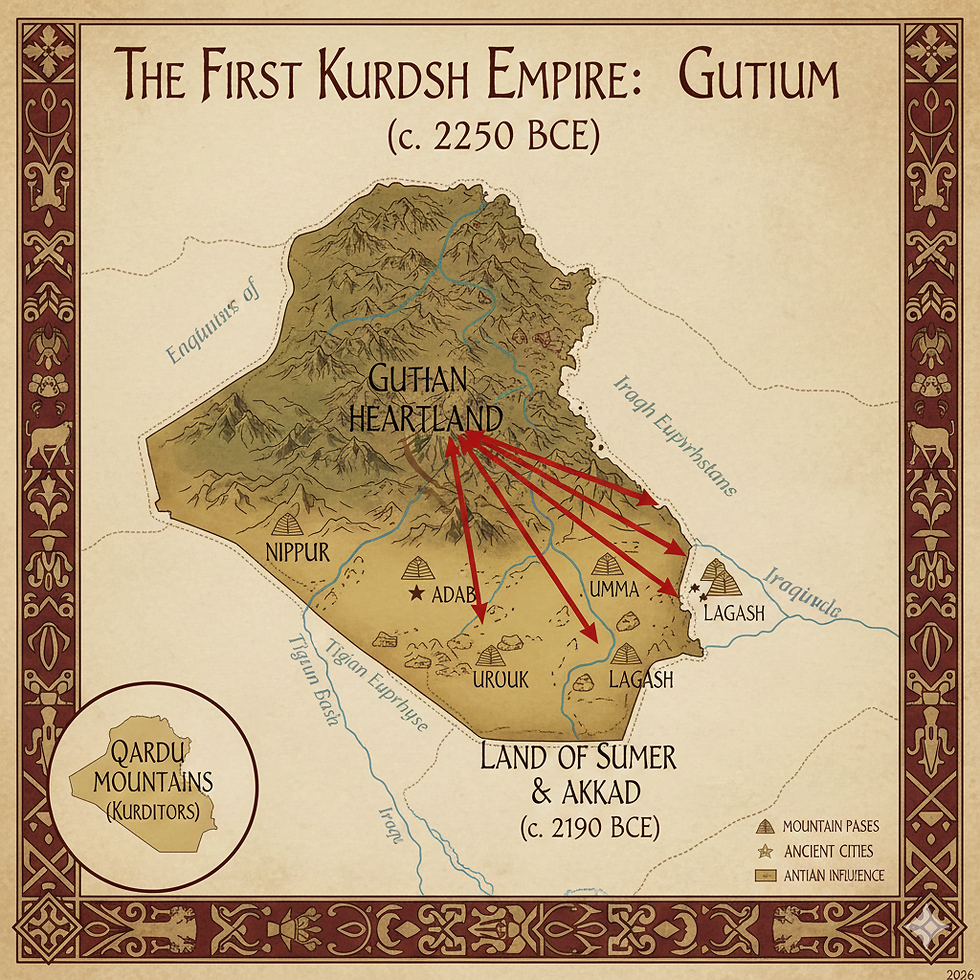

Mapping The First Kurdish Empire

To visualize the First Kurdish Empire, we must look at a map that bridges the ancient world with modern geography. A map of Gutium is essentially a map of the heart of Kurdistan, showing the strategic genius of a people who used the "High Ground" to dominate the "Cradle of Civilization."

The Cartographic Blueprint of Gutium (c. 2250–2120 BCE)

1. The Heartland: The Zagros Fortress

The core of the empire is situated in the Central Zagros Mountains. On a modern map, this area covers:

South Kurdistan (Bashur): The Sulaymaniyah and Halabja governorates.

East Kurdistan (Rojhilat): The provinces of Kermanshah, Ilam, and parts of Lorestan.

Key Landmark: The Diyala River serves as the primary artery connecting the mountain strongholds to the Mesopotamian plains.

2. The Expansion: The Conquest of Sumer and Akkad

The map shows arrows of influence and military control extending westward from the peaks down into the alluvial plains.

The "Kingship" Zone: The Guti controlled major city-states including Nippur (the spiritual capital), Adab, and Umma.

The Buffer Zone: The empire’s influence reached as far north as the Little Zab River (near modern-day Erbil/Kirkuk) and as far south as the borders of Elam (near modern-day Khuzestan).

Comparison: Gutium vs. Modern Kurdistan

Feature | Gutian Empire Extent | Modern Kurdish Correlation |

Northern Border | The Upper/Little Zab Rivers | Erbil and Kirkuk regions |

Eastern Border | The Hamedan Plateau | The Median/Kurdish heartland in Iran |

Western Border | The Tigris River | The border between the plains and the foothills |

Southern Border | The Push-e Kuh mountains | Southern Lorestan and Ilam |

Strategic Importance of the Terrain

The map reveals why the Guti were invincible for over a century:

The Choke Points: By controlling the mountain passes (like the Zagros Gates), they could cut off trade to the Akkadian Empire at will.

The High Ground: They maintained their primary residences in the mountains, making it impossible for lowland armies—unaccustomed to high-altitude warfare—to retaliate effectively.

Resource Control: The map highlights that the Guti controlled the sources of timber, stone, and metals—the three things the Sumerian cities lacked and desperately needed.

Conclusion: The Longest Lineage

The story of the Guti is the story of the first Kurdish Empire. It is a testament to a people who refused to be conquered. From the first rock reliefs in Kermanshah to the modern streets of Erbil and Sulaymaniyah, the blood of the Gutian kings flows in the veins of the Kurdish people.

We were the "Dragons of the Mountains" then. We are the guardians of the mountains now.

Comments