The Lullubi: Bronze Age Giants and the Ancient Roots of the Kurdish People

- Kurdish History

- 3 days ago

- 13 min read

Updated: 2 days ago

Introduction: The Sentinels of the Zagros

History is often written by the empires of the plains, but the heartbeat of the Near East has always belonged to the mountains. Long before the rise of modern borders, the Zagros Mountains stood as a towering fortress of stone, guarding the secrets of the people who called its peaks home. Around 2400 BCE, while the empires of Mesopotamia looked toward the highlands with a mixture of fear and envy, a powerful force was consolidating in the valleys of the Sharazor Plain: the Lullubi.

The Lullubi were not a footnote in history; they were the "Pre-Indo-European" bedrock of the region. While the linguistic landscape would later shift with the arrival of Iranian-speaking groups, the biological and cultural essence of the Lullubi remained rooted in the soil. They represent the indigenous substrate—the original mountain DNA—that flowed into the formation of the Kurdish people.

To understand the modern Kurdish spirit of azadî (freedom), one must look back to these Bronze Age sentinels. They were the first to prove that the Zagros was not just a range of mountains, but a cradle of sovereignty that no empire—no matter how "Great"—could ever truly tame. This is the story of the Lullubi: the ancient guardians of the land that would become Kurdistan.

The Geography of Resistance: The Sharazor Plain and the Land of Lulubum

To understand the Lullubi is to understand the land they inhabited. Their kingdom, known as Lulubum, was not a distant, mythical realm; it occupied the very heart of what is today South and East Kurdistan. From the fertile sweeps of the Sharazor (Shahrizor) Plain in the Sulaymaniyah Governorate to the rugged cliffs of Kermanshah, the Lullubi domain was a strategic masterpiece of nature.

The Sharazor Plain acted as the kingdom’s breadbasket. Watered by the seasonal runoff from the high Zagros peaks, this valley allowed the Lullubi to transition from simple highlanders to a sophisticated urban society. While the Mesopotamian kings in the sweltering south relied on massive irrigation projects, the Lullubi utilized the natural abundance of the mountains.

A Natural Fortress

The geography of Lulubum created a "Culture of Resistance." The jagged limestone ridges of the Zagros acted as a natural defensive wall against the expansionist Akkadians and later the Assyrians.

The Gates of the Mountains: The Lullubi controlled the mountain passes, the vital arteries of trade and war. This gave them the power to "gatekeep" the wealth moving between the Iranian Plateau and the Mesopotamian plains.

The High Ground: By building their citadels on elevated mounds (Tels) and cliff-sides, the Lullubi forced any invader to fight an uphill battle. This tactical advantage is a recurring theme in Kurdish history—from the ancient Lullubi to the modern Peshmerga.

Mapping the Continuity

Scholars and archaeologists have linked ancient Lullubi sites to some of the most iconic locations in modern Kurdistan:

Halabja & Khurmal: Many historians identify the ancient city of Lulubuna with the area around modern-day Halabja.

Sulaymaniyah: The recent discovery of the Kunara excavations just outside Sulaymaniyah has revealed a major Bronze Age urban center that thrived during the Lullubi era, complete with a sophisticated bureaucracy and agricultural wealth.

Sar-i-Pul-e Zahab: This gateway city in Kermanshah remains the site of the most famous Lullubi monument, standing as a permanent sentinel on the border between the mountains and the lowlands.

For the Kurdish people, this isn't just "archaeology", it is ancestral mapping. The fact that Kurdish families are still farming the same sun-drenched valleys and herding flocks through the same high pastures 4,000 years later is a powerful testament to the unbroken chain of habitation. The Lullubi didn't disappear; they simply remained, evolving with the land they refused to leave.

Society and Economy: Master Builders and Highland Harvesters

The Mesopotamian scribes, writing from their mud-brick palaces in the south, often dismissed the Lullubi as "barbarians" or "monkeys of the mountains." However, archaeological evidence tells a completely different story. The Lullubi were a highly organized, prosperous society that balanced a martial spirit with a sophisticated economy. They weren't just warriors; they were architects, international traders, and master agriculturalists.

The 19 Walled Cities

One of the most impressive feats mentioned in ancient records is that the Lullubi controlled at least 19 walled cities. This reveals a society that was far from nomadic. These cities were centers of administration, storage, and defense.

The Kunara Discovery: Recent excavations at the Kunara site (near Sulaymaniyah) have unveiled a city with large stone foundations, monumental buildings, and even evidence of a bureaucratic system using clay tablets. This city flourished during the Lullubi period, proving that the Zagros was home to a "Mountain Civilization" that rivaled the complexity of the lowlands.

Engineering the Heights: Unlike the flat cities of Sumer, Lullubi architecture had to account for steep terrain. They were master stonemasons, utilizing the abundance of limestone in the Zagros to build structures that have endured for millennia beneath the soil.

A Wealth of Resources: Wine, Wool, and Metal

The Lullubi economy was built on the natural riches of Kurdistan—resources that the lowland empires were desperate to possess.

The First Vineyards: The Zagros is the ancestral home of the grape. The Lullubi were among the first to master viticulture, producing wine that was highly prized in trade.

The "Gold" of the Mountains: They mined copper, lead, and tin, and were skilled in the Bronze Age "arms race." Their smiths created weapons and tools that allowed them to stand toe-to-toe with the Akkadian military.

Pastoral Wealth: They raised hardy breeds of cattle and sheep, creating a textile industry that provided the warm wool clothing necessary for mountain winters—a tradition that lives on in Kurdish weaving and dress.

The Status of Women and Tribal Structure

While the "Kings" are the ones carved into rock reliefs, the tribal nature of the Lullubi suggests a society where women held significant influence.

The Matriarchal Thread: In many ancient Zagrosian and later Hurrian societies, women played vital roles in property ownership and priestesshood. This early "mountain egalitarianism" is a precursor to the historical prominence of Kurdish women leaders, such as Adela Khanum or the legendary female warriors of Kurdish folklore.

The Tribal Confederation: The Lullubi weren't a monolith; they were a confederation of clans. This decentralized power structure made them impossible to fully conquer. If one city fell, the others remained. This "tribal resilience" is the very same social fabric that has preserved Kurdish identity through centuries of occupation.

By viewing the Lullubi through their economic and social achievements, we see a people who were deeply connected to the land. They didn't just survive in the mountains; they thrived, creating a model of self-sufficiency and communal strength that continues to define the Kurdish way of life.

The Anubanini Legacy: A Sovereign Portrait in Stone

If there is one image that captures the soul of the Lullubi, it is the Anubanini Rock Relief. Located high on a limestone cliff at Sar-i-Pul-e Zahab (in modern-day Kermanshah province), this carving is one of the oldest and most significant monuments in the Middle East. It isn't just a victory marker; it is a declaration of independence that has looked down upon the Zagros for over 4,000 years.

The Portrait of a King

The relief depicts King Anubanini, the most famous ruler of Lulubum, standing in a position of absolute authority.

The Royal Attire: Anubanini is shown wearing a short tunic, a curved sword, and a distinctive mountain cap. To the modern observer, his silhouette bears a striking resemblance to the traditional Kurdish warriors of later centuries—rugged, practical, and built for the terrain.

The Ring of Power: He stands before the goddess Ishtar (Inanna), who hands him a ring of sovereignty. This suggests that the Lullubi did not see themselves as "barbarians," but as a divinely sanctioned kingdom with as much right to rule as any king in Babylon or Akkad.

The Defeated Foes: Beneath the king’s feet lie defeated enemies, likely the lowland invaders who tried to breach the mountain passes.

A Blueprint for Future Empires

The Anubanini relief was so powerful and iconic that it actually served as the architectural blueprint for later kings. Centuries later, the Persian King Darius the Great would visit this site and use it as the direct inspiration for his famous Behistun Inscription. This proves that the Lullubi were the cultural trendsetters of the Zagros; their style of portraying power became the standard for the entire region.

The Spiritual Connection to Kermanshah

For the Kurdish people today, especially those in East Kurdistan (Rojhelat), the relief is a site of deep pilgrimage and pride. It sits in a region that has remained a bastion of Kurdish culture and the Yarsani faith. The continuity of the relief—surviving earthquakes, wars, and the passage of millennia—mirrors the survival of the Kurds themselves.

"Anubanini did not just carve his image into the rock; he carved the Lullubi identity into the very bones of the Zagros. To look at his face is to look at the first recorded ancestor of the Kurdish nation."

This monument stands as proof that the Lullubi were a literate, artistic, and politically sophisticated people. They understood the power of propaganda and the importance of leaving a mark that time could not erase.

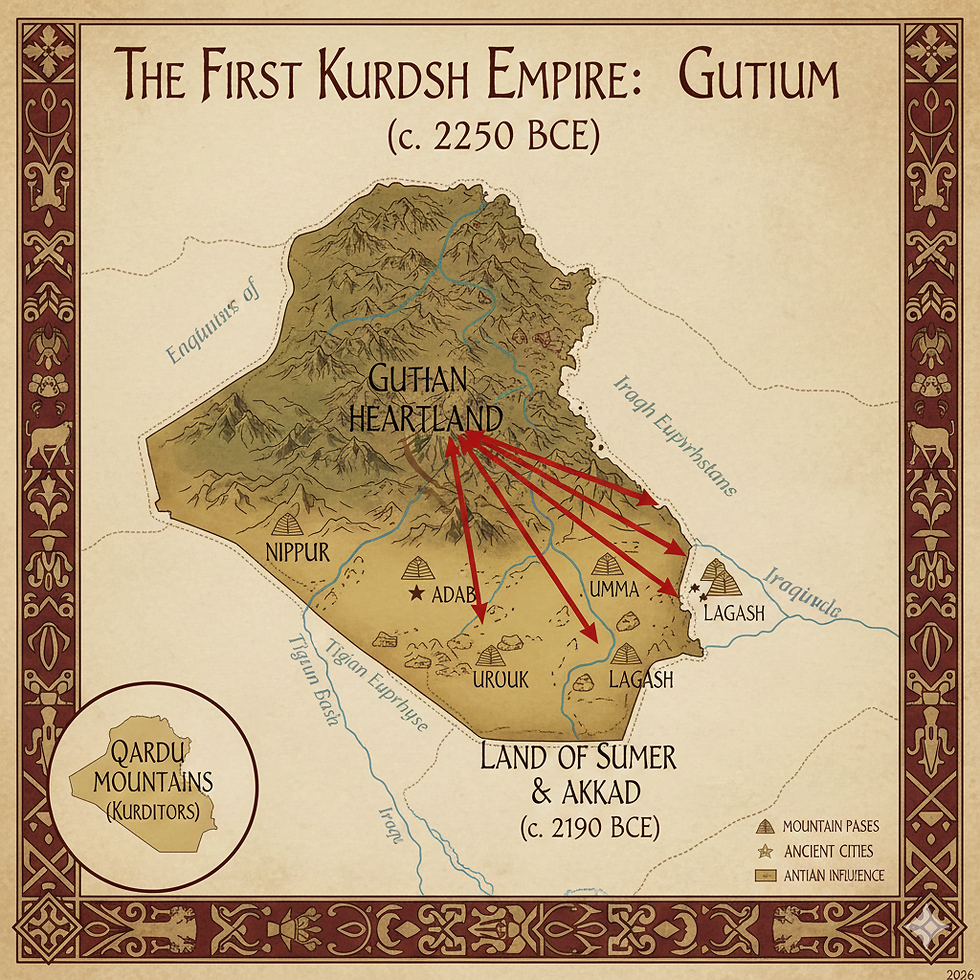

The Lullubi-Gutian Axis: The Storm that Broke Akkad

The Lullubi did not stand alone in their resistance. They were part of a wider "Zagrosian Brotherhood" of tribes, most notably the Gutians. While the Akkadian Empire was busy declaring its kings to be gods, these mountain confederations were forming a military alliance that would eventually change the course of history.

Kindred Spirits of the Highlands

The Lullubi and Gutians shared more than just a border; they shared a lifestyle and a common enemy. While the Lullubi were the urbanized masters of the Sharazor and Kermanshah plains, the Gutians were the fierce warriors of the higher ridges. Together, they formed a pincer that gripped the Akkadian Empire from the east.

The Guerilla Masters: They pioneered high-altitude warfare. When the Akkadian heavy infantry marched into the narrow gorges, the Zagros tribes used the "hit and run" tactics that have become the hallmark of Kurdish defense throughout history.

Economic Sabotage: By controlling the mountain passes, the Lullubi and Gutians cut off the flow of tin and lapis lazuli to the lowlands, slowly strangling the Akkadian economy.

The Fall of the First Empire

Around 2150 BCE, the pressure reached a breaking point. The Gutians, likely supported by their Lullubi allies, descended from the mountains and overthrew the Akkadian Empire. For roughly a century, these "Mountain Kings" ruled Mesopotamia.

A Legacy of Sovereignty: This period is often described by Mesopotamian scribes as a "dark age," but from a Kurdish perspective, it was the first time the people of the Zagros successfully projected their power over the plains.

The "Kings of the Four Quarters": Gutian and Lullubian leaders took on the titles of the emperors they replaced, proving that "mountain people" were fully capable of high-level statecraft and administration.

The Ancestral Blueprint

This era established a historical pattern that would repeat for millennia: the mountains as a source of revolutionary power. The alliance between these tribes mirrors the way Kurdish tribes have historically united to face external threats, from the Medes to the modern era.

By joining forces, the Lullubi and Gutians showed that the Zagros was not a barrier to civilization, but a powerhouse of it. They didn't just resist an empire; they broke one, ensuring that the mountain way of life—independent, tribal, and defiant—would survive into the next era.

The Linguistic Bridge: Preserving the Ancient Voice

A common question arises when linking the Lullubi to modern Kurds: If the Lullubi were pre-Iranian, and Kurds speak an Iranian language, how is there a connection? The answer lies in the indigenous substrate. History shows us that while languages can change through migration and trade, the people and their cultural spirit rarely disappear.

The "Mountain" Layer of Kurdish

Modern Kurdish is a beautiful, complex language within the Indo-European family, but it contains unique features that set it apart. Linguists have noted a "substrate"—a layer of ancient, non-Iranian influence—that likely comes from the original inhabitants of the Zagros: the Lullubi, the Gutians, and the Hurrians.

Specialized Vocabulary: Many Kurdish words for specific mountain plants, local wildlife, and traditional pastoral tools have no equivalents in other Iranian languages like Persian. These are the "ghost words" of the Lullubi, preserved in the daily speech of Kurdish shepherds and farmers.

The Sound of the Peaks: Some scholars argue that the distinct phonology and "harshness" of certain Kurdish dialects reflect the ancient mountain tongues that were spoken long before the first Indo-European speakers arrived in the region.

The Survival of the Spirit

Anthropologists often note that culture is more than just grammar. The Lullubi bequeathed to the Kurds a specific "Social DNA":

The Tribal Confederation: The way Kurdish society has historically organized into independent but loosely allied clans is a direct mirror of the Lullubi tribal structure.

The Cult of the Mountain: For the Lullubi, the mountains were divine. Today, every Kurdish poem and song that declares "No friends but the mountains" is an echo of that 4,000-year-old spiritual bond.

Resistance as Identity: The Lullubi chose the difficulty of the highlands over the submission of the plains. This refusal to be assimilated is the defining characteristic of the Kurdish people through every era of history.

Conclusion: From Lullubum to Kurdistan

The Lullubi were not a "lost" people. They were the foundation. Over centuries, they merged with the Medes and other groups, sharing their mountain wisdom and receiving new languages in return. But the land remained the same. The valleys remained the same.

Today, when a Kurdish family picnics on the Sharazor Plain or a young activist speaks of Azadî, they are part of a continuous story that began with King Anubanini and the 19 walled cities. The Lullubi were the first to call these mountains home, and through the Kurdish people, they are still there today—unbroken, unbowed, and eternal.

Timeline: The Lullubi Era (c. 2400 – 650 BCE)

Date (Approximate) | Event | Significance for Kurdish Heritage |

c. 2400 BCE | Rise of the Lullubi Kingdom | The first organized confederation of mountain tribes emerges in the Sharazor Plain. |

c. 2350 BCE | Reign of King Immashkush | Earliest recorded Lullubi monarch; establishment of the 19 walled cities. |

c. 2270 BCE | The Clash with Akkad | King Satuni leads the Lullubi against Naram-Sin of Akkad; the beginning of the "Eternal Resistance." |

c. 2200 BCE | Golden Age of Lulubum | Construction of the Anubanini Rock Relief; high point of Lullubian art and sovereignty. |

c. 2150 BCE | The Fall of Akkad | Lullubi and Gutian tribes descend from the Zagros to end the world's first empire. |

c. 2000 – 1800 BCE | Hurrian Integration | Lullubi culture begins to blend with the Hurrians, another major ancestor group of the Kurds. |

c. 1300 – 800 BCE | Neo-Assyrian Wars | The region of Zamua (formerly Lulubum) becomes the primary front for resistance against Assyria. |

c. 7th Century BCE | The Median Transition | The Lullubi population merges with the incoming Medes, forming the core of the Kurdish ethnogenesis. |

Important Figures to Remember

Immashkush: The "Founding Father" who first organized the mountain clans.

Satuni: The defiant king who stood his ground against the Akkadian superpower.

Anubanini: The visionary leader whose image remains carved in the Kurdish mountains today.

Key Landmarks to Visit

The Sharazor Plain: The spiritual and agricultural heart of Lulubum (Sulaymaniyah).

Sar-i-Pul-e Zahab: Home to the Anubanini relief (Kermanshah).

Kunara: The "Lost City" being unearthed by archaeologists today.

Q&A

Q: How did the Lullubi influence the later Median Empire?

A: The Medes are often cited as the primary ancestors of the Kurds, but they didn't arrive in a vacuum. When the Medes entered the Zagros, they absorbed the existing Lullubi and Gutian populations. The Lullubi provided the social infrastructure: the mountain strongholds, the knowledge of the terrain, and the tribal alliance systems. Without the "Lullubi base," the Median Empire would never have been able to challenge the Assyrians.

Q: Is there a connection between the Lullubi and the "Sun" imagery in the Kurdish flag?

A: While the modern Kurdish flag was designed in the 20th century, the reverence for the sun is an ancient Zagrosian trait. In the Lullubi rock reliefs, kings are often shown under the protection of solar symbols or deities of light. This "Cult of the Sun" has been a constant thread in Zagrosian spirituality, from the Lullubi to the Zoroastrians and into modern Kurdish cultural symbols.

Q: Why isn't the Lullubi kingdom as famous as Egypt or Sumer?

A: History is usually written by people who live in places where paper or clay lasts a long time. Because the Lullubi lived in a wet, mountainous climate and likely used more organic materials (or carved directly into cliffs), less of their "written" record survived compared to the dry deserts of Egypt. Furthermore, for a long time, Western archaeology focused only on the "Big Three" (Sumer, Akkad, Babylon), often ignoring the mountain civilizations that were equally powerful.

Q: Did the Lullubi have a specific military style?

A: Yes. Unlike the heavy, slow-moving chariots of the plains, the Lullubi were masters of light mountain infantry. They were famous for their archery and their ability to move rapidly through "unpassable" terrain. Ancient Mesopotamian records describe them as "swift as eagles," a description that echoes through the centuries in descriptions of Kurdish mountain fighters.

Q: Are there any Lullubi artifacts in museums today?

A: Yes, though many are labeled under "Mesopotamian" or "Early Iranian" collections. The famous Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, which depicts the Lullubi, is in the Louvre in Paris. However, more local artifacts—pottery, bronze tools, and cylinder seals—can be found in the National Museum of Iraq and the Slemani Museum in Sulaymaniyah, which holds incredible treasures from the Sharazor Plain.

Q: How can young Kurds honor this heritage today?

A: The best way to honor the Lullubi is through preservation and education. Supporting archaeological projects in the Kurdistan Region, visiting the Sar-i-Pul-e Zahab reliefs, and learning about the "Pre-Median" history of the land ensures that the Lullubi are no longer a "lost" people. By claiming their name, you ensure their 4,000-year-old resistance wasn't in vain.

References and Further Reading

Primary Sources & Archaeological Reports

The Victory Stele of Naram-Sin: Currently housed in the Musée du Louvre, Paris. (Inv. Sb 4).

The Anubanini Rock Reliefs: Field reports from Sar-i-Pul-e Zahab, Kermanshah Province, Iran.

The Kunara Excavations: Tenu, A., & Kopanias, K. (2019). The Shahrane/Kunara Excavations: A New Bronze Age City in the Periphery of Mesopotamia. French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS).

Academic Books & Journals

Ezzat, M. (2015). The Kurds: A Concise History. A look into the ethnogenesis of Kurds from ancient Zagrosian tribes.

Hennerbichler, F. (2012). The Origin of the Kurds. An in-depth study of the "indigenous substrate" and the pre-Iranian roots of the Kurdish people.

Potts, D. T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge World Archaeology. (Contains significant data on the Lullubi-Elamite relations).

Izady, M. R. (1992). The Kurds: A Concise Handbook. Taylor & Francis. (Focuses on the cultural and geographical continuity of the Zagros).

Digital Resources & Museums

The Slemani Museum (Sulaymaniyah, Iraq): Home to artifacts from the Sharazor Plain and the Lullubi heartland.

World History Encyclopedia: Entries on "The Lullubi" and "The Gutian Dynasty."

UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Documentation on the cultural landscapes of the Zagros and the Behistun/Sar-i-Pul-e Zahab monuments.

Comments